The Measles Outbreak Strategic Response Plan 2021-2023

April 1, 2021

The Measles Outbreak Strategic Response Plan 2021-2023 is published by WHO with input from key stakeholders, including M&RP partners (the United States CDC, the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF, American Red Cross), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It serves as a roadmap for advocacy, resource mobilization, and timely interventions to control, recover from, and prevent measles outbreaks.

The bold Measles and Rubella Strategic Framework (2021-2030)

November 1, 2020

The bold Measles and Rubella Strategic Framework (2021-2030), a measles-specific strategy under IA2030, is endorsed by SAGE and published to identify past shortfalls and accelerate progress on stagnating measles vaccine coverage and stronger health systems over the next decade to realize a world free from measles and rubella.

The Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030)

August 1, 2020

The Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA2030) is adopted by all Member States during the 73rd World Health Assembly, with measles outbreaks being a primary indicator of where particular interventions are needed. IA2030’s goals include halving the number of children who have not received a single vaccine dose, achieving 500 introductions of new vaccines, and achieving 90 percent coverage for basic childhood vaccines.

The Region of the America

April 29, 2015

The Region of the Americas is the first in the world to be officially declared free of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome.

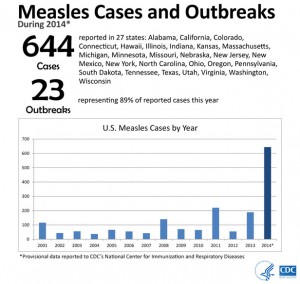

A Record Year for Measles in Elimination Era

December 31, 2014

The CDC reported 644 cases of measles in 2014, the highest number of U.S. cases in any year since measles was declared eliminated in 2000. December ended with a threat that would extend into 2015: between December 15 and December 20, visitors to Disneyland in Anaheim, California, were exposed to measles by an as-yet-unidentified index case. Cases quickly spread as primary contacts returned home and spread the illness to secondary contacts across the country. A small, unrelated outbreak of measles in Mitchell, South Dakota, added to the case count as the year ended.

The Ministers of Health in the Regional Committee of the South-East Asia

March 2, 2013

The South-East Asia Region adopted a goal for measles elimination by 2020, marking the first time that all 6 regions of the world have established goals for measles elimination.

Immunization partners (WHO, UNICEF, CDC)

March 14, 2012

Immunization partners (WHO, UNICEF, CDC) established the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) that includes a goal for measles and rubella elimination in 5 of the 6 regions of the world by 2020.

The MI became the Measles & Rubella Partnership

March 2, 2012

The MI became the Measles & Rubella Partnership (M&RP), and published the Measles & Rubella Strategic Plan, 2012-2020, expanding the vision to include a world without measles OR rubella.

The last endemic measles

March 2, 2002

The last endemic measles case occurred in the Region of the Americas.

The American Red Cross, CDC, UNF, UNICEF and WHO

March 1, 2001

The American Red Cross, CDC, UNF, UNICEF and WHO agree to be the founding partners of the Measles Initiative (MI) with a vision of a world without measles

Endemic Measles Eliminated From United States

March 14, 2000

Continuous transmission of measles was halted in the United States. However, U.S. residents remained at risk for infection from imported cases.

WHO established the Measles and Rubella Laboratory

March 1, 2000

WHO established the Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network (LabNet), based on the Global Polio Laboratory Network model. When it started, it included 60 laboratories worldwide.

The Pan American Health Organization

March 1, 1994

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) set goal for measles elimination in the Region of the Americas.

Measles Cases Drop Dramatically

March 14, 1981

With the Measles Elimination Program having set a date to eliminate the disease from the United States by October 1, 1982, current statistics seemed promising. In April of 1981, the number of reported measles cases was down an “unprecedented” 80% from the previous year. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that only 778 cases were reported in the first 14 weeks of 1981, while 3,897 had been reported during the same period the previous year. Unfortunately, the disease would prove more difficult to conquer than researchers had hoped, and the goal of U.S. measles eradication by 1982 would not be met.

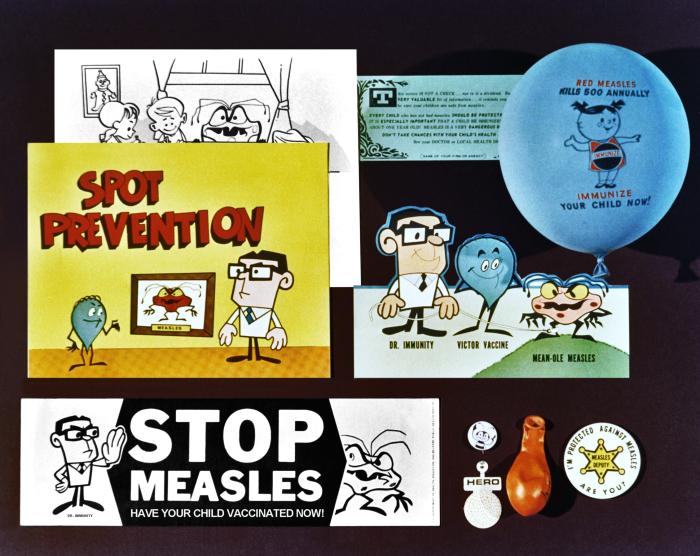

Measles Targeted for Elimination

March 1, 1978

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared a goal of eliminating measles from the United States by 1982. Although this goal would not be met, widespread vaccination drastically reduced the incidence of the disease, and it would be declared eliminated in the country by 2000.

MMR Combination Vaccine Debuts

March 1, 1971

The U.S. government licensed Merck’s measles, mumps, and rubella combination vaccine (M-M-R). In an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers reported that the vaccine induced immunity to measles in 96% of vaccinated children; to mumps in 95%; and to rubella in 94%. Additionally, initial tests in 1968 had already shown that adverse reactions from the MMR vaccine were no greater than from any of the single vaccines.

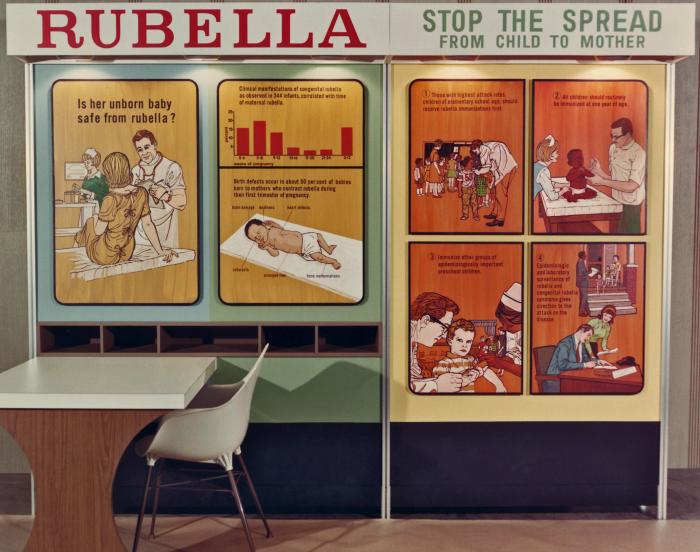

Rubella: First Vaccine Licensed

March 1, 1969

Maurice Hilleman, working at Merck, modified a rubella vaccine virus from Paul Parkman and Harry Meyer, scientists at the Division of Biologics Standards. The vaccine entered commercial use in 1969-1970. A year later, in 1971, the MMR vaccine was licensed, and protection against measles, mumps and rubella was provided at the same time, via one shot.

U.S. Rubella Outbreak Infects Millions

March 1, 1964

U.S. Rubella Outbreak Infects Millions: A massive rubella outbreak in the United States initially failed to draw serious attention. A Time magazine article encouraged rubella parties, even recommending strategies so that “especially all the little girls get the infection.” Unfortunately, despite warnings about keeping infected children away from pregnant women, nearly 50,000 women in vulnerable stages of their pregnancies were infected with rubella during the outbreak, leading to thousands of miscarriages and even more children being born with severe damage. At least 8,000 were born deaf, 3,500 deaf and blind; the total number of congenital rubella syndrome cases reached 20,000. Over the course of the outbreak the country tallied approximately 12.5 million cases of rubella and more than 2,000 deaths. Resulting medical costs reached the billions

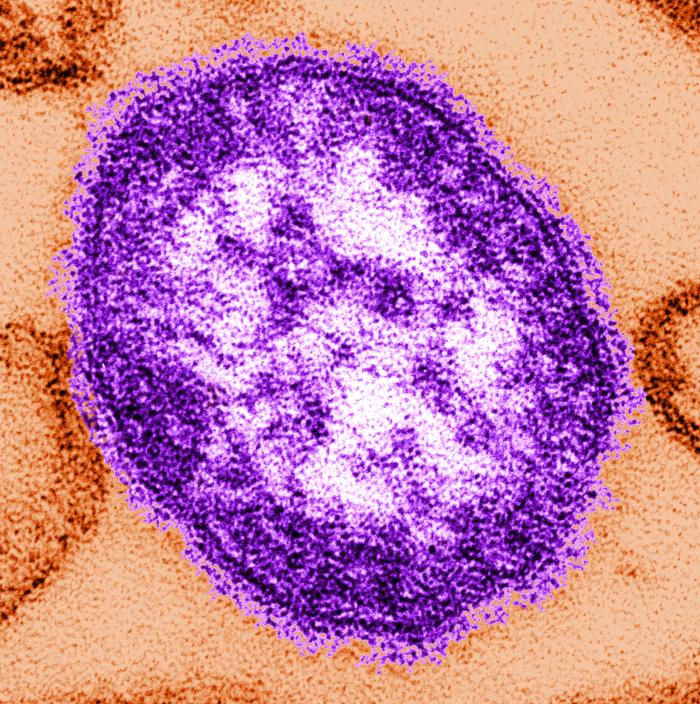

Measles Vaccine Licensed

March 1, 1963

After demonstrating its safety and efficacy, first in monkeys and then humans, John Enders and colleagues declared their measles vaccine capable of preventing infection. Their Edmonston-B strain of measles virus was transformed into a vaccine licensed in the United States in 1963, and nearly 19 million doses would be administered over the next 12 years.

Rubella Virus Isolated

March 1, 1962

Maurice Hilleman and Eugene Buynak isolated the Benoit strain of rubella virus. They hoped to develop an inactivated virus vaccine, but eventually gave up this idea in favor of an attenuated virus vaccine.

First Measles Vaccine Is Tested

October 15, 1958

Sam Katz, MD, an infectious disease specialist working with Thomas Peebles and other researchers in the Boston lab, tested the first version of the lab’s vaccine on mentally retarded and disabled children at a school outside of Boston. Each of the 11 vaccinated children developed measles antibodies, but nine also developed a mild rash—the vaccine didn’t cause full-blown measles, but it did cause symptoms. The researchers realized the virus used for the vaccine had to be weakened even more.

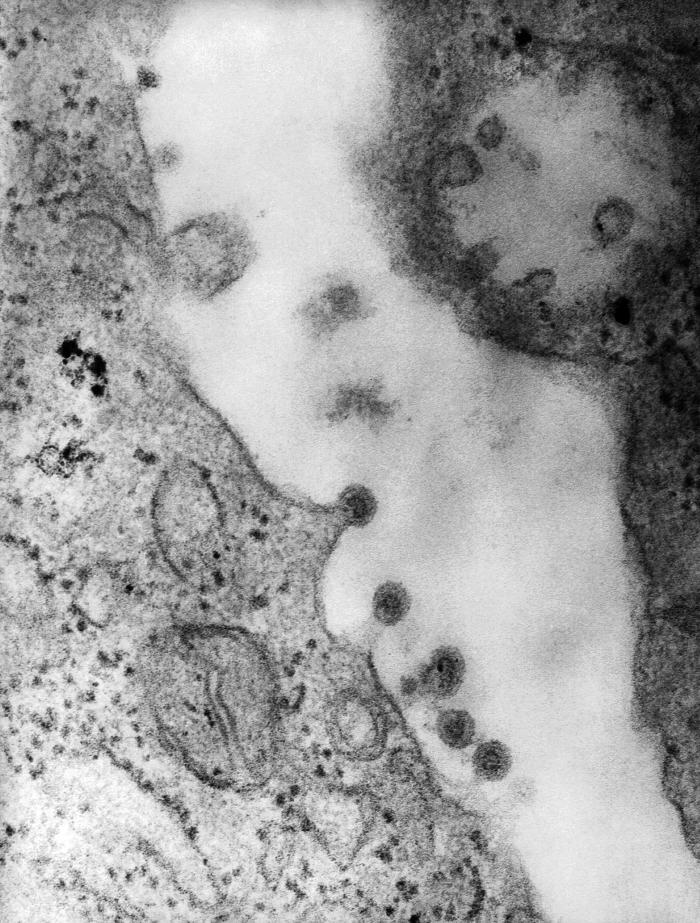

Thomas Peebles Isolates the Measles Virus

March 14, 1954

Thomas Peebles, MD, working in a laboratory at Boston Children’s Hospital, was asked by lab director John Enders to isolate the virus responsible for measles. Peebles learned of an outbreak at a private school outside of Boston and, after getting permission from the principal, collected blood samples from the sick students, telling each boy: “Young man, you are standing on the frontiers of science.” Peebles attempted for weeks to obtain the virus, and on February 8, succeeded. He collected blood containing the virus from 13-year-old student David Edmonston. Eventually, the collected measles virus would be isolated and used to create a series of vaccines.

Rubella Implicated in Congenital Defects

March 1, 1941

Rubella Implicated in Congenital Defects: Australian ophthalmologist Norman McAlister Gregg noted a surprising number of infants suffering from cataracts in his practice. Gregg later overheard mothers in his waiting room discussing the cases of rubella they’d had during their pregnancies in the midst of an outbreak the year before. After further investigation, Gregg linked rubella during pregnancy to congenital cataracts. His observation was the first of what eventually became a collection of reports linking rubella during pregnancy to various congenital defects. The risks were overwhelming: infection with rubella during the first trimester of a pregnancy resulted in a greater than 2 in 3 chance of a baby afflicted with congenital rubella syndrome. Of the syndrome’s various symptoms and complications, ranging from blindness to heart disease to neurological abnormalities, deafness was the most common.

Rubella: Researchers Demonstrate Transmission of Disease

March 1, 1938

Japanese scientists S. Tasaka and Y. Hiro used throat washings from children sick with rubella to transmit the disease to healthy children. The causative agent of the disease, however, remained unidentified.

Measles Continues to Spread in the U.S

March 14, 1916

Measles killed nearly 12,000 people in the United States in 1916, 75% of them younger than five years old. Estimates of the percentage of measles patients who suffer complications from the disease have ranged from 15% to as high as 30%. Serious complications include pneumonia, encephalitis, and corneal ulceration.

Measles-specific Antibodies Identified

March 1, 1916

French researchers Charles Nicolle, MD, and Ernest Conseil, MD, showed that measles patients have specific protective antibodies in their blood. The researchers then demonstrated that serum from measles patients could be used to protect against the disease.

Rubella:The Naming of the “Little Red

March 1, 1841

The name “Rubella,” meaning “little red,” was first used to describe an outbreak at a boys’ school in India. Later, this would be referenced by English surgeon Henry Veale in the Edinburgh Medical Journal (Volume 12, 1866) documenting the history of an epidemic of “Rötheln.” Veale proposed that the name Rubella replace “Rötheln,” citing the need for a name that was easy to write and pronounce.

Infectious Nature of Measles Shown

March 1, 1757

Scottish physician Francis Home, MD, transmitted measles from infected patients to healthy individuals via blood, demonstrating that the disease was caused by an infectious agent

Sydenham Documents Measles Infection

February 28, 1676

Sydenham Documents Measles Infection: English doctor Thomas Sydenham, MD, publishes Observationes medicae circa morborum acutorum historiam et curationem (Medical observations on the history and cure of acute diseases). Although the Persian physician Rhazes was the first to attempt distinguishing smallpox from the measles, Sydenham was the first to do so successfully and in detail. He also recorded details about and distinguished the disease from scarlet fever.

Prelude Version 2.3.2

Prelude Version 2.3.2